Video

Summary

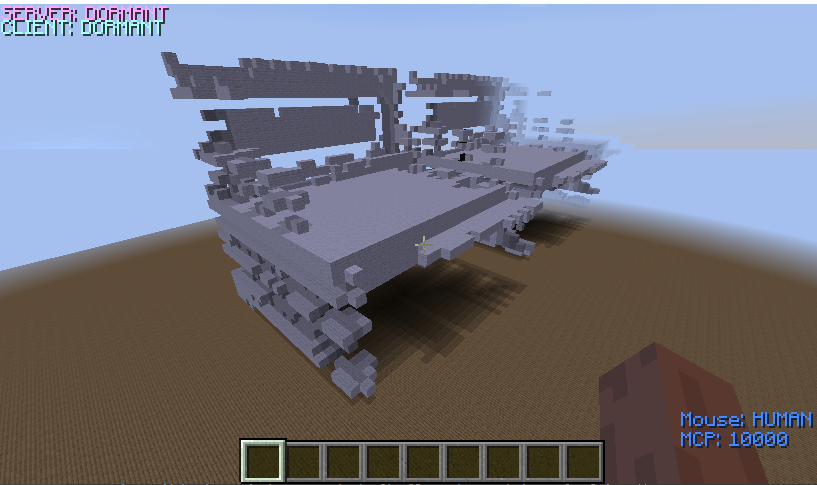

The goal of our project was to generate 3D structures using a Generative Adversarial Network(GAN). After the type of object has been decided the appropriate pre-trained model will be loaded and the generative model is inputted with random noise. The output of the generative model will be a 3D matrix consisting of a probability for each value. The probabilities are rounded such that 0’s will be interpreted as an empty space while 1’s will be interpreted as occupied space. Lastly the 3D matrices are rendered into Minecraft in a 30x30 area.

Approach

We started by using a dataset of 3D objects (chairs and tables) in the Object File Format (.off). The format is used for representing a geometric figure by specifying the surface polygons of the model. The format of a .off file is fairly simple: a list of all vertices, followed by a list of faces with the corresponding vertices. The .off objects were then converted to voxels using our own Python scripts. The scripts work by determining whether a voxel lies on a surface of the mesh. First the dimensions of the 3D mesh are scaled to fit within a 30x30x30 grid.

The surfaces of the mesh are then converted into voxels by checking whether nearby points overlap with the given surface. We can check whether they overlap by calculating the normal vector of the surface, and projecting the possible points onto this vector. If the magnitude of the projected vector is with a certain threshold this means the point exists on the same plane as the surface.

However, to check whether the point actually exists within the bounds of the surface we then calculate the barycentric coordinates of that points in relation to the surface. If all of the barycentric coordinates are positive this means the point is within the bounds of the surface.

Here is are the equations used in these calculations:

If both of these conditions are true then a voxel is placed at the points. The output of the script is a 3D matrix with dimensions of 30x30x30; the matrix is binary encoded, meaning that the entries that are 0 signify an empty block and the entries that are 1 signify a cube.

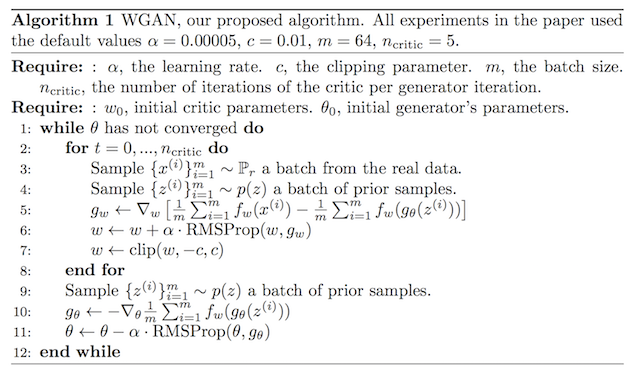

The model we use is a Wasserstein generative adversarial network (WGAN). We found this model provided us with better quality generations as compared to when we used a normal GAN model in our status report. The WGAN differs from a normal GAN in several ways. Firstly, it utilizes a Wasserstein loss function where as previously we used binary cross entropy. Wasserstein loss is defined here:

By doing so the discriminator is replaced with a critic. Instead of determining whether is real or fake the critic will score the input based on the realness of the input. The generator now trains to minimize the difference in score between real and generated voxel models. Overall, this makes the model more stable and less sensitive to changes to hyper parameters and model architecture.

Another difference with WGAN’s is that the critic model is actually trained more than the generator model. The reason for this is to ensure the critic is optimally trained through each step of the training. The reason for this is that with WGAN’s critic must be near optimal otherwise training becomes unstable. A poor critic will lead poor assessments of loss on real and generated voxels, which will cause the generator to train inefficiently. Therefore we need to ensure the critic is near convergence before training the generator.

Lastly, we attempted to implement an Auxiliary Conditional GANS (ACGANS) in conjunction with our WGANS. This would have made it possible to train multiple classes of object with a single training model. However, we were not able to achieve good quality results with this model, and instead decided to train 2 separate WGAN models for chairs and tables.

Evaluation

Our the process for evaluating the performance of our model revolves around looking at the loss rate of each of our models (the critic and generator), and adjusting the model depending upon which model is lacking in strength. Also we access the stability of the model by checking whether the difference between the critic loss rate of real and generated voxels converge.

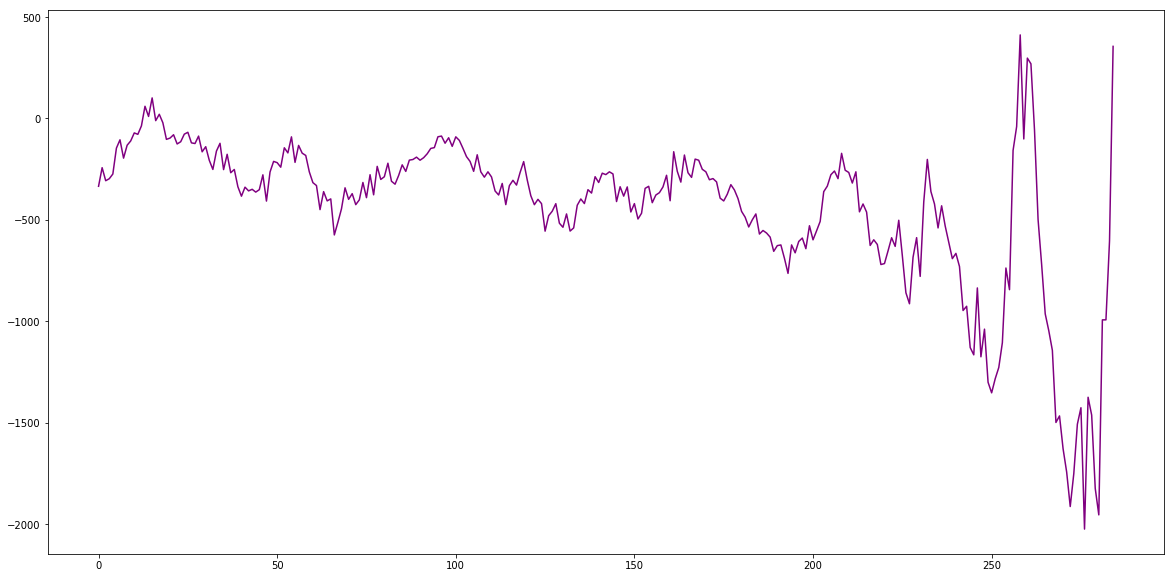

Here you can see a graph of the critic loss rate of one of our training sessions. (Overall critic loss rate is difference between generated and real loss rate.)

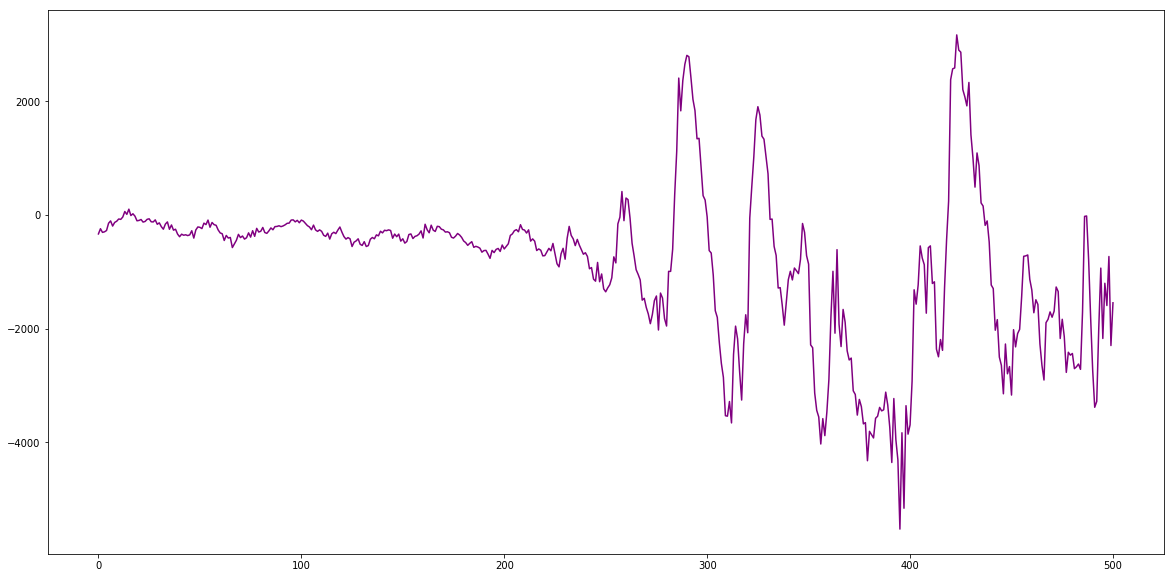

From this image we can see the loss rate becomes more and more erratic as the training goes on. This indicates to us that the training is becoming unstable. This could be causes by several things. The critic may not be optimized enough, in which case we would have to train the critic more. The critic may not be powerful enough, in which case we would add more layers to the critic. In this case we changed tried training critic more. Instead of training the critic 5 timers per generator training we increased this to 10 times. Here are the results:

You can see that this was successful because the critic loss rate does become more stable after some more training. The values are no longer diverging and fit within a smaller range.

However, something we noticed was that even if the difference in generated voxel and real voxel loss was loss, this does not always mean the generated voxels look visually appealing. The loss rate tells us how well the model is performing however is not always a good indicator for how well the images look.

For example during this generation, the critic loss rate was about 250.

In this generation the critic loss rate was about 543.

The latter image looks significantly better despite having a worse loss rate. We believe this occurs because of the dataset we used. Our dataset is very limited only have around 900 chair models and 500 table models, and within the dataset the models were heavily varied. For example, some chairs had wheels and rotated where as some other chairs had 4 legs.

Given more time we could have solved this problem by expanding our dataset. A potential approach to this could be reusing data by slightly transforming it. An example of this could be slightly rotating each 3D model. This would reduce the variability in the dataset, while also increasing the amount of data.

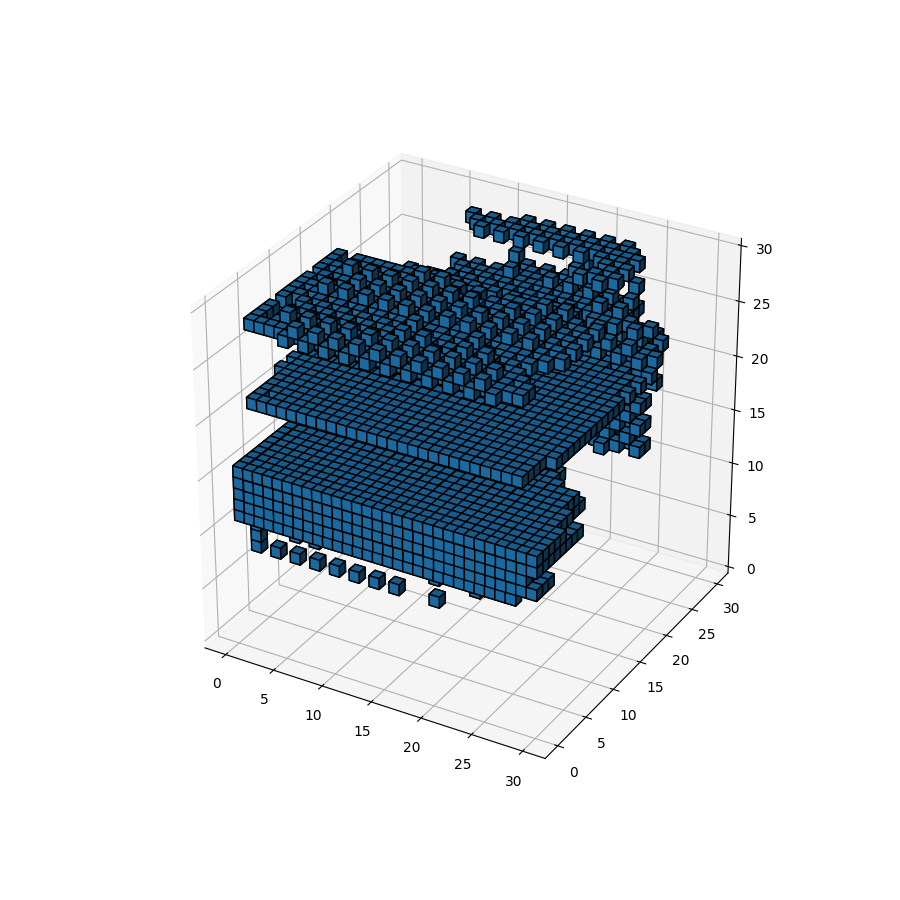

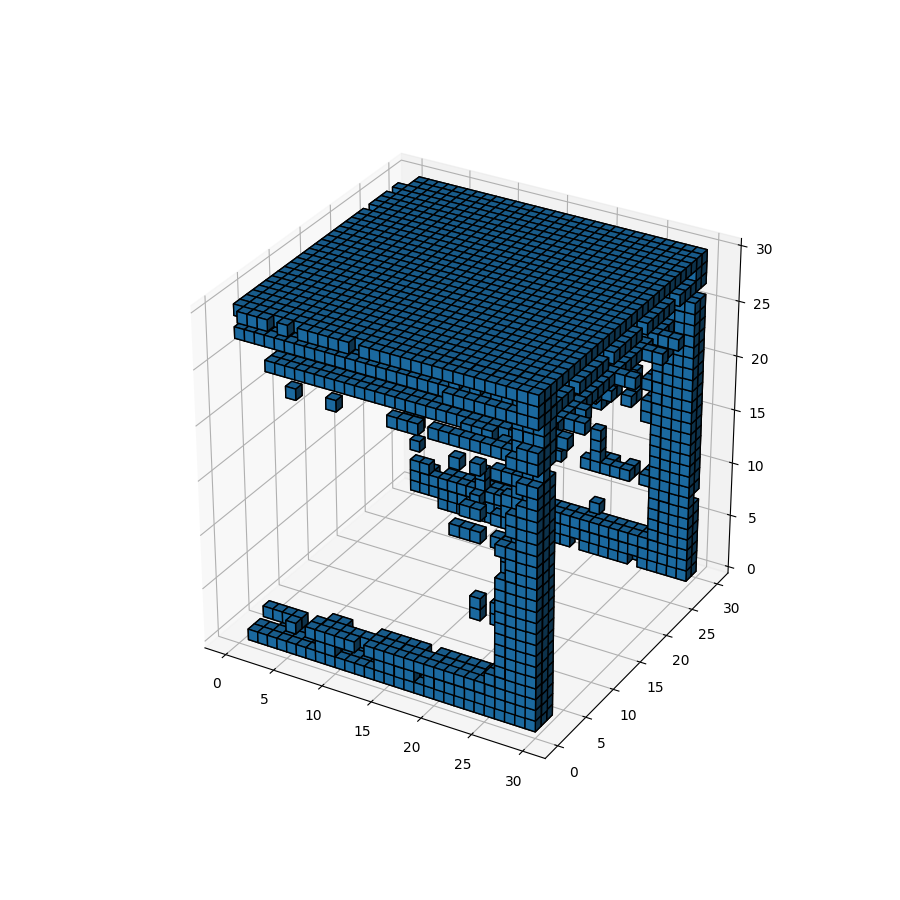

Lastly, here are the results of some of our generations rendered in Minecraft:

Tables:

Chairs: